Many years ago, Franz Kafka imagined a creature that was elusive, and remained tantalizingly out of reach, so that its exact nature was never quite discerned:

The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat almost like a human face, and small and oval; only the teeth have any power of expression, whether they are concealed or bared.

from the The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges.

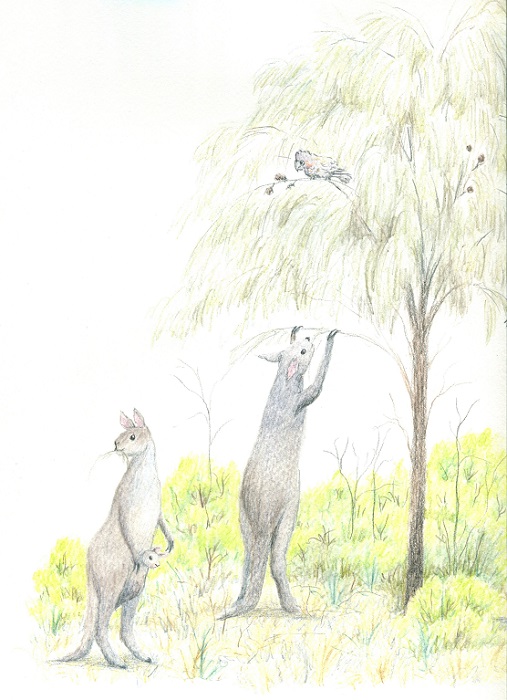

I’m not sure if Kafka ever heard of the giant short-faced kangaroo, known only from fossils, and first described by Richard Owen in 1845. Like a human, this beast had a reduced snout, forward-facing eyes, and mobile shoulders that allowed it to stretch its forelimbs above its head. Anatomical features also suggest that it stood upright and walked instead of hopped. But like many long-extinct animals, its true nature remains elusive.

Artist’s impression of the giant short-faced kangaroo, Procoptodon goliah, that lived in south-eastern Australia during the Pleistocene. By Paula Peeters, watercolour pencil on paper.

Procoptodon goliah, the giant short-faced kangaroo, lived in Australia in the Pleistocene (about 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago). Standing at 2 to 3 m in height, it had fewer and longer digits on its forelimbs than a living kangaroo, and only one toe on each massive foot – somewhat like a horse. Like Kafka’s beast, the teeth of Procoptodon are certainly expressive and curious, as they have no modern analogues. Debate continues about what they ate: grass, trees or saltbush? But whatever it was, one would think these giant kangaroos were reaching up to get it¹.

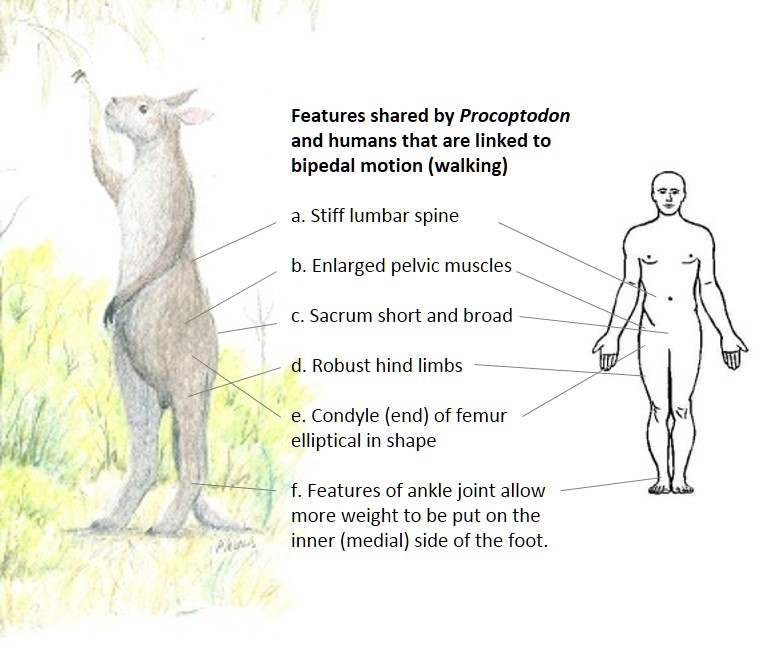

Close examination of Procoptodon’s anatomy has revealed many features that living kangaroos – the ones that hop – do not have. Many of these features also differentiate humans (who walk upright) from their closest ape relatives (who do not). Features that help bipedal movement (walking or running) include: robust hind limbs (which allow the animal’s full weight to be borne on one leg at a time); a short and broad sacrum and stiff lumbar spine (this helps the spine to resist rotational forces); enlarged pelvic muscles and an ankle joint that puts weight on the inner side of the foot (to balance the body on one leg); and elliptic femoral condyles (which reduce the load on the knees).

Procoptodon also shares features with other living marsupials that have an upright posture (tree-kangaroos and koalas), such as modified pelvic muscles (to hold the trunk upright), and enlarged epipubic bones (which are thought to support their bellies – including pouches).

Features linked to bipedal motion that are shared between the giant short-faced kangaroo, Procoptodon goliah, and humans.

Large (extant) kangaroos (at 80 – 90 kg body mass) are already placing great stress on their muscles and tendons by hopping, and appear to be near the upper body size limit for this type of movement. So Procoptodon (body mass up to 250 kg) may have been mechanically unable to hop. Also, the forelimbs and especially the hands of Procoptodon were so specialized that they probably could not be used for the pentapedal (four-limbs-and-a-tail) motion that living kangaroos use when they move slowly. It seems that bipedal motion – walking and running – could have been the solution to these mechanical limitations.

However, we may never really know if Procoptodon walked, hopped or ran because there are no living animals that share its enigmatic anatomy. Like Kafka’s animal, this beast moves only in our imaginations, its muscles and tendons turned to dust thousands of years ago.

1. So what did Procoptodon eat? My hunch is depicted in the illustrations for this post. But that is another story, for another day.

References:

Borges, J.L. (1974) The Book of Imaginary Beings. Penguin Books, Ringwood.

Janis C.M., Buttrill K., Figueirido B. (2014) Locomotion in Extinct Giant Kangaroos: Were Sthenurines Hop-Less Monsters? PLoS ONE 9: e109888. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109888

Prideaux, G. J. (2004) Systematics and Evolution of the Sthenurine Kangaroo. University of California Press, Berkeley.

Prideaux, G.J. and Warburton,.N.M. (2010) An osteology-based appraisal of the phylogeny and evolution of kangaroos and wallabies (Macropodidae: Marsupialia). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159: 954–987.

Rich,P.V. and van Tets, G.F. (1985) Kadimakara, extinct vertebrates of Australia. Pioneer Design Studio, Lilydale.

Sanson, G.D. (1983) Evolution of feeding adaptations in fossil and recent macropodids. Ch. 13, pp. 489-506 In: Rich, P.V. and Thompson, E.M. The fossil vertebrate record of Australasia. Monash University, Clayton.

More on the web about giant short-faced kangaroos:

A big ass kangaroo by Jan Freedman

Beautiful digital artwork of Procoptodon goliah by Roman Uchytel

Fascinating! I wonder how it escaped from predators? Standing and walking short distances upright is one thing, but running to escape predators – especially with a thick tail (did they have a thick tail to help them stand or for balance?) – would be tricky if they’re running on two toes (albeit modified as you mentioned).

If the tail was strong enough, I guess it could kick? But it would still need to be able to flee from danger.

Hi Dayna the researchers who looked at locomotion of the giant roos included a drawing of one running in their paper, which suggests they thought it was possible. Since P. goliah was so big it may not have had many natural enemies. But during the Pleistocene there was the giant monitor lizard, terrestrial crocs and the marsupial lion, which all might have preyed on the big roos. I think your idea of kicking certainly has merit – those hind legs were large and strong. Whatever the big roos were doing, it was successful for a few million years, so they were more than a match for the predators. Until people turned up, some think… Cheers, Paula

Fascinating article. I can just imagine what it be like to see this animal coming out of the scrub.

Thanks Carol. If only we could jump into the TARDIS one day (preferably with David Tennant), travel back in time and get a glimpse of one. Cheers, Paula